The Spinghar Mountains never seemed to be in the same province as Jalalabad, though

they were. Not once in my Peace Corps days did I meet anyone who had been there,

either as traveler or resident. They came up in conversation only as a bandits’

lair. Always in plain view, the range seemed as beautiful and untouchable as the

moon, especially in the light of that celestial body but really at any time of day.

Those impossibly high peaks exuded an ethereal energy, more shimmer than substance,

silver as much as white, when everything in the overheated lowlands, outside a few

patches of green, had by late spring dried into one faded shade of brown or another.

So near but so far, the Spinghar made me think of places with the opposite quality,

like home or heaven.

Perhaps they made a similar impression on Osama bin Laden. His last known location,

when I returned to Afghanistan the summer of 2003, had been at Tora Bora in the

middle of those mountains. It was the better part of an all-day drive from Jalalabad,

largest town in the East and capital of Nangrahar Province. Even that estimate was

theoretical. The Special Forces detachment in town doubted our leased pickups could

make it. On a dismounted, night patrol the team left the track that followed a stream

bed—too susceptible to ambush—for a goat trail above it. They had to

pull back short of Tora Bora when their medic fell some 30 feet. The Camelbak that

threw off his balance saved him from serious injury when he landed on it.

The Provincial Reconstruction Team (PRT) took a different approach: it wanted to

build a school in the area. The Director of Education proposed a village where the

road left the lowlands for Tora Bora. Much easier and safer to get to, he noted,

and, unlike Tora Bora, the elders had come to see him about it. The previous PRT

had it on their list. As he made his case, I wondered if that village at the foot

of the mountains was one our planes had bombed in the hunt for bin Laden and if

its elders might be the bunch who had driven out a clan whose leader we had met

near a smugglers’ village east of Tora Bora, closer to the Khyber Pass. The

Director was too politic to mention that, and neither Eddie, who represented another

agency, nor the Special Forces captain would talk about Tora Bora 2001. For our

men under arms, unhappy history made for ancient history.

Washington also set its sights elsewhere, namely, on Iraq. Like al-Qaeda, we couldn’t

be everywhere at once. So we made do with a few stay-behinds, 40 of us for three

provinces, everyone armed but me, and 39 more than I could have imagined my first

time in country.

Still—Eddie wasn’t pushing the Tora Bora site purely for tactical reasons.

He knew the attention it would attract. Just as nobody up the chain talked about

Tora Bora, nobody forgot about it, either. Those rhyming, faraway syllables haunted,

like Osama himself and other unfinished business. Eddie’s interpreter had

actually gone there the previous year. It hadn’t been a friendly visit, but

at least everybody who went—and then some—came back.

Lately Osama was looking more and more like some failed prophet, a loser stuck in

the past, and Eddie’s contacts were saying the mountain men up that way had

started to rethink their position. In confirmation of the solitude in which they

now found themselves, they’d heard that our numbers were down, especially

in Nangrahar, and that we were talking as if we were once again going to have money

to throw around. No direct payments this time. Money for projects.

Like Eddie, the Governor preferred the site at Tora Bora. So did the PRT commander

and I, though I recommended we do both schools. But since neither our aid agency

nor my employer, the State Department, had funds for that, our military was footing

the bills. Even their budget for projects was running low, and their headquarters

at Bagram needed to spread it around.

Tora Bora got the nod.

If we traveled by land, we’d have to return the way we went in. That was a

problem anywhere in country, especially in the highlands. And the road to the mountains

passed through a district known to harbor al-Qaeda sympathizers. Mines had gone

off there, aid workers had been sniped at, and our Special Forces had raided a few

compounds. The UN placed it off-limits to their own personnel, and the aid workers

followed suit.

Helicopters represented a much safer option. None were based in the East, however,

and Bagram had never provided any for a PRT mission out of Jalalabad. But Tora Bora

was hard to turn down. One day the word came from on high: we’d get our Chinook.

::

None of us knew what to expect. Which made it even more important that we go. The

farther you ventured from the towns, the more the Pashtuns indulged in a predisposition

to xenophobia. In the East, especially, they identified with the resentments and

delusions of grandeur that their Arab co-religionists promoted. But they also had

a tradition of going with a winner, or a sponsor. That could be us if we tried.

Sarwar, Eddie’s interpreter and the only one on our manifest to have been

there, agreed. One thing we did know: the helicopter wouldn’t be dropping

us off at the doorstep of the world’s most notorious terrorist. He was too

smart for that. Or too far gone. If anybody thought maybe, just maybe, we’d

find a clue, he kept it to himself.

9/11 was another thing we kept to ourselves—what we were doing at the

time, how it might have affected us personally. Our work gave us more than enough

to talk about. For me, that meant no unwelcome return to the question I heard often

in the first days after the attacks—did I know any of the dead or injured?

I didn’t. My blessing. Someone else’s pain.

For family and friends, probably for all of us, comprehension came in stages. Like

so many others, I saw it on TV, the television on a high shelf in a windowless office

in the Pentagon. I was on a detail from State. We were wrapping up a hastily-called

meeting about the Twin Towers when Flight 77 vectored in on a path headed straight

for our office. Reinforced pillars in the new wedge stopped it one ring short of

our own.

Two officemates and I stayed by the phones, assuming, in a last stand of old think,

we’d be needed. The only sounds I remember after the initial thud were us

talking and the TV. An eerie quiet prevailed in the hallway outside. Usually we’d

hear footsteps, voices. The smoke that wafted in was thin and wispy. It clung to

the ceiling, thickening only slowly. Then its daddy, dark and agitated, barreled

down the corridor. A sweaty, smudged man ran up to our door shouting, “Get out!

Get out!”

You had to drop down low to see your way through.

But you couldn’t let stuff like that get personal except in the sense that

everything was personal. With everybody. Everybody had baggage. Either you got over

it or you ended up twisted, like Osama. Most Afghans must have found his fanaticism

odd, or exotic. Even so, his hosts probably liked the promise that Islam would rise

again. They definitely liked the money. They liked playing with the big boys. That

we came at all, and that we achieved so much with so few, must have surprised them.

For Tora Bora we had another surprise, a recognition that we each had something

to offer the other. We didn’t expect any surprises in return, though of course

you never know till you go.

The PRT commander designated the captain of one of his two civil-affairs teams as

mission commander. The captain’s four-man team covered Nangrahar, and I’d

accompanied them on several trips to the districts. The PRT’s sergeant in

charge of security and a soldier who almost never got out from behind the radio

also made the roster. With me, that filled the PRT’s allotment. The Chinook

could carry only so many, and we were told to expect add-ons from Bagram.

The Special Forces detachment, plus Eddie and Sarwar, claimed half the seats. Eddie

wouldn’t miss this for the world, and Sarwar went where his boss went. Special

Forces provided prowess and firepower should that be necessary. This time, however,

they’d have to do it without the mobile reaction force they had trained. Besides

Sarwar, the only Afghans assigned to the mission were the civil affairs interpreter

and one for the Special Forces. The entire detachment—nobody remained behind

for this one—drove to the airfield loaded for bear. But they couldn’t

leave town until Bagram gave authorization, which sometimes came at the last minute

if at all.

::

Nangrahar was paved in two places—the driveway to the Governor’s palace

and the runway at the airport the United States built, complete with control tower

and waiting room, in our competition with the Soviets during the Cold War. Then

as now, the facility was closed to the public. In the Seventies, only biplanes flew

out of it. The Afghan army used them for parachute training. Having undergone that

in our own army, I pestered a major I knew to take me up for some cross-cultural

bonding. Sorry, he’d demur, it’s classified. Fifteen years later, when

the mujahedin fired their first Stinger missiles, bringing three Soviet gunships

down in flames, it happened at Jalalabad field. Later still, some nine years after

our trip, U.S. forces took off from here on the raid that finally got Osama. By

that time we had turned it into a major base. In 2003 Americans made an appearance

only when a flight came in.

::

For once the helicopters arrived on time, in sync with the rising sun. The Chinook

swooped in low and then eased itself onto the tarmac, blowing up dirt we never noticed

just standing around. As its Apache escort circled overhead and the rest of us tromped

up the Chinook’s ramp, Special Forces hung back by their radio. Their captain

was still negotiating with Bagram. Nobody there could make a decision. The civil

affairs captain asked the crew chief for more time.

Sorry, the chief said after checking with the pilot. The choppers were on a tight

schedule.

Hailing his Special Forces counterpart, the civil affairs captain asked, through

a thumb-up, thumb-down gesture, for a sign.

The other captain flicked his hands outward, leaving the palms up. His head canted

to the side. He hadn’t been told yes. He hadn’t been told no. This was

killing him, you could see.

The rotors churned up the dust and debris again as the Chinook powered for liftoff,

and the detachment turned away to shield their eyes.

A minute or two out, they got the green light. We could see the runway and terminal

through the settling dust. Movement there might have been somebody signaling. I’m

sure they called on the radio. Too late. There was no going back. Instead of our

in-house operators, Bagram sent us two female soldiers on a joyride and a New Zealander

toting the kind of high-tech rifle the rear echelon tended to get their hands on.

The empty seats left room to stretch out and take in the scenery. Unfortunately,

Chinooks weren’t built for tourism. The Plexiglas bubbles that served for

windows let in light but no clarity. Unless you were in the cockpit or by the open

crew stations up front, the best view was through the back door when the ramp was

down. A crewman sat on the lip, his feet dangling, a mounted machine gun by his

side. A line tethered him to the frame. Looking around him and his gun, we could

at least see where we’d been and more than that when we were circling.

From our height—about 800 feet, I’d estimate—Jalalabad showed

far more vegetation than we ever saw going down its dusty streets. Much of it grew

behind compound walls. The compounds thinned out as we moved south, leaving vacant

lots and uncultivated fields in-between. Soon there wasn’t much of anything

at all. The broad basin at Nangrahar’s core, veined with green where there

was irrigation, gave way to balding foothills spotted with scrub and scrawny trees.

Some ten miles to the west, unrecognizable from that angle and distance, was the

high school—its replacement, actually—where I’d taught in the

Peace Corps. It probably sat closer to the mountains than any other volunteer’s

place of work at the time. The towns and valleys were challenge enough. Even there

you could feel isolated, cut off. It wasn’t that Afghans were unfriendly.

They just didn’t understand.

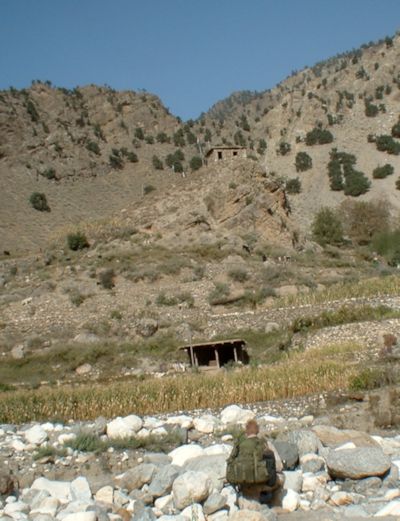

We followed a canyon into the highlands. Winding and climbing, it broadened and

then narrowed. I spotted a few animal paths and what looked to be a shepherd’s

hut. No vehicles, no houses. As we continued to climb—barely enough to crest

a treeless ridge—a cool draft began pushing out the hot air that enveloped

us at the start of the journey. Another ridge and then the canyon broadened again.

The Chinook corkscrewed down, offering us a view of the snow that gave the mountains

their name (spin means white in Pashtu; ghar is mountain).

Those summits lay ahead, farther than we would go. We were descending over a stream

that was more rocks than water. Although the canyon widened here into a knobby bowl,

the smaller valley that channeled the stream was too susceptible to flooding to

do anything with. Terraced fields stair-stepped the hills above it. Most crops had

been harvested; stubble carpeted the fields. Dust coated everything. Cows, sheep,

and goats grazed where they could. Not a pack animal in sight.

The Chinook settled on rocks between the stream and its banks.

PRT soldiers spread out to form a perimeter, the Bagram contingent filling in as

directed by our security sergeant. From behind boulders at the high-water mark the

soldiers looked up at bearded men on their haunches looking down at us, their expressions

as stony as their surroundings. None of them appeared to be armed. That was a change

from the Seventies, when practically every able-bodied male in the countryside was

packing, the main exception being police if you saw any and Peace Corps.

The Chinook lifted as soon as the last soldier’s boots hit the rocks. The

Apache had been waiting, high in the air.

I joined Eddie and Sarwar, neither of whom had taken cover. As always, Eddie dressed

for the occasion, this time in blue jeans and a short-sleeve shirt under a navy-blue

armored vest covered by another vest, an outdoorsman’s type with all kinds

of pockets. A plastic Camelbak tube protruded from under his collar, and an M-4

rifle sling pressed on the other shoulder. His sunglasses may have cost a pretty

penny but they looked cheap, the kind you’d wear at the beach and good enough

for government work. His pistol, if he had it, was concealed. He and Sarwar, whose

bearing varied between thuggish and puckish, sported pakols, the saucer

cap Massoud made famous and General Hazrat Ali was often seen wearing. Ali, who

once worked for Massoud, had led a militia commissioned by American operators to

kill or capture Osama when he fell back to these hills after 9/11. Despite Ali’s

failure to close, and allegations he may even have connived in Osama’s escape,

he parlayed his connections into command of the so-called Eastern Corps based just

down the road from the airport. Both he and Sarwar favored stone-colored Western

clothing with cargo pockets in all the right places, a striped green gunman’s

scarf at Sarwar’s neck. Both carried AK-47s. The one accessory that distinguished

him from Ali and indeed all Afghans in the East other than Special Forces interpreters

was an armored vest, which he wore under his jacket. The extra heft lent him gravitas.

He took a sip from his Camelbak tube, blue like Eddie’s.

On top of a small, rocky butte in front of us, white and green pennants fluttered

above what Sarwar said was a shrine to Arab “martyrs” killed two years

earlier. His previous visit had been on a raid that snatched the village headman

and two of his sons. Eddie’s predecessor might have been on that. Or special

operators came in for the mission. Or it could have been all Afghan. Eddie didn’t

go into details, and Sarwar followed his lead.

As the helicopters disappeared over the ridgeline, a man zigzagged down a path to

greet us. It was Jan Gul, Sarwar whispered, the guy they had snatched. Perfect.

He had a thick, black beard, sturdy build, and the easy self-confidence of a headman

who was probably the son of a headman. After the small talk he waited for us to

explain ourselves.

You must get a lot of thunderstorms, I remarked, trying indirection for a change.

Sarwar translated. Up in the mountains like this, I added. We’d seen and heard

them from the smugglers’ village. You could see them from town if you climbed

the ladder to the PRT roof.

More than Jalalabad, Jan Gul conceded.

Lightning?

He smiled, wondering where this was headed. We’re used to it, he said.

Eddie told him we’d heard they might need a school.

Jan Gul’s smile broadened. He had come to know Americans at the detention

center in Bagram. Did he find us inscrutable, or totally predictable? Probably a

little of both. Whatever, here we were—again. In daylight this time. Come

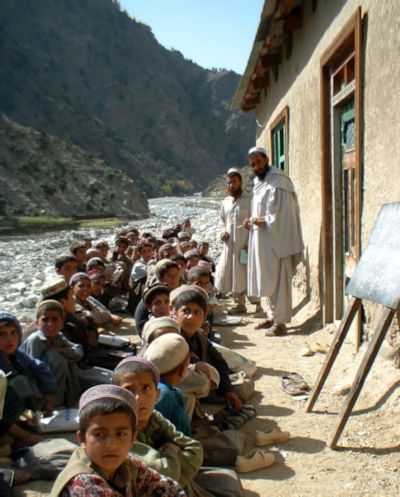

on, he urged, and he led us up the hillside to a dirt lot beside a mosque where

about a hundred boys, arranged in rows, were studying under the shade of a mulberry

tree. They were younger than the ones I’d taught, boys who’d be in their

late forties to early fifties if still alive. I recognized the faces, the look.

They were staring at the unknown, the X factor in lives they thought they had figured.

In the old days Western trousers were required. The students slipped them on, outside

the schoolhouse, over pajama-like pants they wore at all other times. No books,

and they were responsible for supplies. Here, everyone had a UNICEF bag with notebook

and pencils. A teacher with chalk and a blackboard watched over them. They were

learning to read and write, he said.

The captain presented a box of textbooks a church group had sent from the States.

They were in English, of course. The teacher leafed through the pages, nodding and

smiling at the incongruity. Except maybe in Kabul, English hadn’t been on

the curriculum since the Soviet invasion.

Another fifty or so boys sat in two rows on an earthen shelf between the mosque

and the stream. Two long-bearded teachers dressed in white, one with a book, one

with a stick, presided. In contrast to the first teacher and most men hereabouts,

they wore skullcaps instead of pakols. They were mullahs, not so willing

to talk as the secular teacher.

Both sections of this school without walls looked out on the stream, the stones

that lined it, the terraced fields, scattered huts, and the snowy mountains beyond.

The boys saw it all the time, so they hardly noticed. In the lowlands school shut

down for the summer. Here schools closed in the winter.

A rough track followed the stream. It too closed in the winter. Trucks but not SUVs

could negotiate it the rest of the year, we learned from Jan Gul. Most traffic was

on foot, locals mostly, a few strangers every once in a while. Pakistan lay around

the bend. No border guards or government representatives up this way. Above and

below us, pockets of men gathered to observe and discuss our visit. Many had long

hair, which you never saw in Jalalabad anymore. None smiled, at least not for our

benefit. Don’t worry, Jan Gul assured us; if al-Qaeda returned, he’d

tie them up and hand them over.

Eddie had heard to the contrary. That might not be so easy, he remarked.

The whole village would help, Jan Gul explained.

All of them? Eddie asked. There were more men around than you’d expect

from the few houses scattered about. The helicopters must have drawn them.

Most, Jan Gul replied. I’m their headman.

Like many Afghan males with some years on them, his eyes never stopped twinkling,

and an unexpressed humor underlay almost everything he said. He found our presence

amusing, and the reason we gave for it unconvincing. But he liked to accentuate

the positive. Two years after the B-52s, a year after his capture, we had come around.

Also, Afghans are good at telling you what you want to hear. A foreigner, you might

be ignorant enough to believe. At least you might think twice. Even if not, such

talk made pleasant background for meetings with friends as well as strangers. It

was like shaking hands. It’d be rude not to.

Boys from other villages attend, the teacher said when I asked. More would come

if there were a schoolhouse, he added. The lowland site the Director of Education

preferred would do nothing for Tora Bora. No mountain boy would walk that far to

school.

About a half day’s march, we figured. That’d be our way out if the helicopters

didn’t return. What with weather, breakdowns, and competing priorities, we

could never be sure. Last month, for example, American helicopters ferried a VIP

delegation to Jalalabad for the inauguration of the Afghan Army’s first recruiting

station in the East. When it came time to fly the VIPs back, Bagram radioed that

conditions were too windy. Hold on: VIPs didn’t spend the night in places

like Jalalabad. It wasn’t so much dangerous as incommodious. The ranking American,

a general and a large man, especially when compared to the Afghans, kept up a good

front. He joked about this kind of thing happening all the time. What he didn’t

say was that when it did, it was usually the Afghans’ fault. This time it

wasn’t. I had to admire his grace under stress. That might have changed, of

course, once he made it to Bagram. Anyway, the Deputy Minister of Defense got on

his satellite phone. In less than an hour Afghan helicopters left over from the

Russians whisked our visitors away.

So we each packed two days’ worth of meals ready-to-eat and water bottles,

sleeping bag, and cold-weather clothing. Everybody except Eddie. What he didn’t

have on his person, Sarwar would provide. Fortunately for me, who did back exercises

every evening to be able to sleep at night, I carried neither weapon nor ammo. My

contribution to the public good consisted of an Iridium and spare battery, as nobody

else had a satellite phone and the military radios didn’t always get through.

The plan, if stranded, was to overnight a few kilometers outside Tora Bora and walk

out the next day.

Jan Gul led us to his house, the biggest in the village and the only one with two

stories. It wasn’t easy to spot these structures from a distance, built as

they were from the same clay and stone as the hillside they clung to. Also, they

weren’t that numerous, and crops were laid out to dry across the roofs.

In contrast to the gray, khaki, and dehydrated green that dominated its surroundings,

the interior of Jan Gul’s home was decorated with crepe-paper flowers and

red, yellow, and purple tinsel like you’d see at a toddler’s birthday

in the States. A woman’s touch, perhaps. The room needed it. There was no

electricity, and the winters got too cold for large windows. That the house had

any at all was interesting. Despite Tora Bora’s reputation as a ungoverned

borderland beyond the reach of the law, home construction here showed little of

the paranoia you saw in the rural lowlands, where people hunkered behind high, thick

walls with loopholes to shoot from but no exterior windows other than maybe a small

one in a second-story guest room for those who could afford it. During the day family

rooms took in light from the compound courtyard. Tora Bora had neither courtyards

nor compounds. Its climate called for a closed center.

Over milk tea Jan Gul talked casually about his captivity the way a suburban neighbor

might about his vacation. Eventually Bagram let him and his sons go—for lack

of evidence, I suppose. He showed us a document attesting to his release.

His sons weren’t so talkative. Of a dangerous age, they had the disturbed,

distant eyes I’d seen in other mountain villages. Too much intermarriage,

perhaps. Or too little to do.

When Jan Gul excused himself to join relatives and others who had gathered outside

the door, Sarwar talked about his previous time here. Matching our host’s

mood, he could have been describing a panty raid. The raiders came on foot, at least

for the last part of their journey, at night while the villagers slept.

That may have been the raid described in Kill Bin Laden, a book published

in 2008. In it the author’s team captured, in Tora Bora in 2002, an arms dealer

and his sons accused by their neighbors of having hidden a wounded Osama for three

days and then helping smuggle him across the border into Pakistan. The book also

reported an earlier foray to exhume graves at a martyrs’ shrine in hopes of

finding a match with Osama’s DNA. And it claimed that plans for 9/11 were

hatched in Tora Bora. In 2012 another book—No Easy Day: The Firsthand Account

of the Mission That Killed Osama bin Laden—would mention a ground

and air assault on Tora Bora in 2007 in response to a report of a tall man roaming

the hills in a long, white robe.

Even in my ignorance I sensed the near past, like the near future, all around. But

apart from the martyrs’ tomb, there was no sign of the devastation that news

accounts had led me to expect. There was none of the craters, rubble, or amputees

I’d seen in Kabul. The name Tora Bora covered a substantial area, Jan Gul

had explained, and the caves that sheltered al-Qaeda were high above the dwellings.

If residual damage lay nearby, he was too considerate a host to point to it, and

we didn’t want to reopen old wounds. Not on our first visit. And first visits

were about all we did.

Jan Gul came back to say he was arranging a meal.

We’d have to go, the captain cautioned, when the helicopters came. That might

be within the hour.

We had to stay for lunch, Jan Gul insisted. The Pashtun code demanded it.

A sheep had been slaughtered.

The captain accepted on the condition we ate beside the landing zone. Helicopters

didn’t wait.

::

Elders, men, and boys spread cloths over the stones below a bank by the side of

the stream. They brought roasted mutton and fresh-baked bread. It was delicious.

What about the school? the villagers asked. They were looking for a commitment.

You’ll have to cooperate, Eddie said.

Absolutely, they pledged.

Earlier they had shown us a plot of land near the mosque. One man owned it, they

said. Very expensive.

We suggested they pitch in to buy it. Persuade the owner to lower the price for

a good cause.

The village had no money, they claimed.

What about the girls? I asked. Here, unlike in the lowlands, a visitor could see

that women and girls made up half the population. Although they stayed in the background,

either alone or gathered in twos or threes and peeking around tree trunks, bushes,

boulders, cows, and houses, the bright red, green, and blue of their clothes made

them easy to spot. Their lips—you could see it in the young ones—pressed

in concentration as their eyes kept returning to our two female soldiers, who had

wrapped diaphanous green scarves around their heads and torsos.

We’ll have a room for them, the elders promised.

And a teacher?

Yes.

Any now going to school?

Not yet. They need their own room.

Heads turned. We heard the helicopters before we saw them.

You also have to cooperate on al-Qaeda and Taliban, Eddie reminded.

Absolutely.

There they were, Apache and Chinook.

Everybody stood. We shook hands and gathered our gear.

Talk could lead to more talk, and that would be progress. Our hosts were astute

but not so consciously clever as the smugglers we’d met. Not only did farming

cultivate a different kind of intelligence, but also the highlands fostered an

independence, almost an indifference to the outside world.

Civil affairs hired a contractor to build the school. Everybody understood we couldn’t

buy or even rent Tora Bora that cheap. We just wanted to plant a seed. We had come

to the point where our practice, if not our policy, was forget about what you did,

thought, or felt; tell us what were you going to do and then do it. We applied that

to ourselves as well as to those we engaged. In this way we moved on.

In revising my report, the Embassy in its wisdom placed Pakistan north

of Tora Bora. And they had me describing the villagers as bitter. Philosophical,

I would say. Wait-and-see. But bitter? That was for losers. Like mountain men everywhere,

they were preservationists. Isolationists. Modernity would come, witness us and

bin Laden, in fits and starts. At the end of the day it didn’t matter how

you arrived. What mattered was when you left, how you left, and what you left behind.

—The opinions and characterizations in this article are those of the author

and do not necessarily represent official positions of the United States Government.

Two names have been changed.

—Essay (minus the following photographs) was previously published in the

Spring/Summer 2014 issue of the James Dickey Review, and is reprinted

here by permission of the author.

“Neighborhood Watch” © by Frank Light.

All rights reserved.

Photograph is protected by international copyright conventions.

|

“Martyrs’ Shrine” © by Frank Light.

All rights reserved.

Photograph is protected by international copyright conventions.

|

“School with a View” © by Frank Light.

All rights reserved.

Photograph is protected by international copyright conventions.

|

— Like a number of the author’s other published pieces, this one is

adapted from a draft memoir entitled Adjust to Dust: On the Backroads of

Southern Afghanistan.

is now writing his way through retirement. His work has been published or accepted for

publication in Even the Smallest Crab Has Teeth (an anthology of Peace

Corps nonfiction), Make: A Literary Magazine, WLA (War, Literature, and the

Arts), Mosaic Art & Literary Journal, Beetroot Journal, O-Dark-Thirty, The

Greensilk Journal, Consequence magazine, and Amsterdam Quarterly.

Additional biographical details appear in the essay above.