|

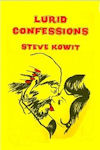

All poems on this page were previously published in Lurid Confessions

and are republished here by permission from Mary Kowit.

|

Carpenter Press (1983);

Serving House Books (2010)

|

|

| |

World-class award-winning poet, teacher, and activist Steve Kowit continues to be “a major

figure in poetry in America today,” as SHJ founding editor Duff Brenna says.

“He was also the best lecturer and commentator on the craft of creative writing

that I’ve ever seen in action.”

Kowit’s poetry collections include The Dumbbell Nebula,

The Gods of Rapture: Poems in the erotic mood, and The First Noble Truth.

He also wrote one of America’s most popular books on writing poetry, In the Palm

of Your Hand: The Poet’s Portable Workshop.

Lurid Confessions, Kowit’s first full-length poetry collection, had

two printings with Carpenter Press, one in 1983 and the other in 1984, but had been

out of print ever since—until 2010.

“It’s been our loss not to have access to the wit and insights of so

many excellent poems,” said the editors at Serving House Books. They were proud

to publish a new soft-cover edition of Kowit’s

Lurid Confessions, released in July 2010.

“Treat yourself,” says Brenna, “take a look and be prepared to

shake your head in wonder. Kowit is brilliant, but he also has a UNIQUE sense of

humor that will have you rolling with laughter.”

This past February, at the invitation of Ricki Rycraft, I did a reading at Mt. San

Jacinto College and afterwards we sat around at Ricki’s house in Menifee with

Duff Brenna and Clyde Fixmer, old friends from the days when Duff, Clyde, and I

taught together at San Diego State University. Ricki’s a short story writer,

Clyde’s a poet, and In 1990 Duff published The Book of Mamie to rave

reviews, a profoundly moving novel that knocked me off my feet. He’s written

half a dozen splendid novels since.

The four of us were chatting and laughing when Duff mentioned that he owned a copy

of Lurid Confessions. I was shocked, shocked that he even knew of the book,

let alone owned a copy. I mentioned offhandedly that for years I’d been wanting

to send that long-forgotten book, my first full collection of poems, out in the

mails again on the off chance that some press might be willing to reprint it. Duff

was immediately interested. He said it was a book he’d always liked a good

deal and that he might be able to help. I could see from his face that a happy idea

was brewing. Two days later I got an email from him and another one from Tom Kennedy

(another terrific novelist), and a third email from Walter Cummins, novelist, short story

writer and Editor Emeritus of The Literary Review. Walter had been kind

enough, years ago, to publish in The Literary Review “Stolen Kisses,” an

essay of mine about the pleasures and hazards of literary cross-fertilization. He

had recently started a publishing venture, Serving House Books, and asked me to

send him, on Duff and Tom’s recommendation, a copy of the book. So that’s

how Lurid Confessions got its second life. I am enormously grateful to

all of them for having urged these poems back into the world.

For that original 1983 edition, I conceived the silly cover art, Bodhidharma and

lady friend. (Michael Previte, if you’re out there somewhere in this world,

thanks for that charming drawing!) But in the original Carpenter Press version it

was mistakenly printed sideways, an annoying error that I fixed by printing up a

wrap-around paper cover with the art sitting the way it should. Needless to say,

I’m delighted to see that error corrected. My beloved wife Mary’s frontispiece,

that equally silly drawing of Madame Blavatsky as a young girl, is also from the

original edition. It’s based on an illustration she found in a Mexican comic

book. I still nod my head at the epigram from Henry Miller and still find the one

from the Amida Sutra heartbreakingly true, and I still think the blurbs on the back

cover make precisely the statement the book wants. And that old snapshot of me also

on the back cover will do well enough: like the poems themselves, it’s a younger

and somewhat lighter-of-spirit version of who I am now. As for the poems, I’ve

cleaned up some of the punctuation, corrected three spelling errors, reversed two

lines, and changed a couple of words. Other than that the poems are as they originally

appeared.

There is nothing much more that needs to be said. I am, of course, delighted that

you are holding Lurid Confessions in your hands. My hope is that some of

these poems will touch you or make you smile or bring you back with some small jolt

to your own life, and that whatever time you devote to this little book will not

be poorly spent.

For Mary, for my friends, in loving memory of my parents, & for you.

Blue things are blue, red things are red...

That is what we call Paradise.

—Amida Sutra

I expect the angels to piss in my beer.

—Henry Miller

Tonight, sick with the flu & alone, I drift

in confusion & neurasthenia surrendering

to the chaos & mystery of all things,

for tonight it comes to me like a sad but obvious revelation

that we know nothing at all.

Despite all our fine theories we don’t have the foggiest

notion of why or how anything in this world exists

or what anything means or how anything fits

or what we or anyone else are doing here in the first place.

Tonight the whole business is simply beyond me.

Painfully I sit up in bed & look out the window

into the evening. There is a light on

in Marie’s apartment. My neighbor Marie, the redhead,

is moving away. She found a cheaper apartment elsewhere.

She is packing up her belongings.

The rest of the street is dark, bereft.

In this world, nothing is ruled out & nothing is certain:

a savage carnivorous primate bloated with arrogance

floating about on a tiny island

among the trillions of islands out in the darkness.

Did you know that the human brain was larger 40 millennia back?

Does that mean they were smarter?

It stands to reason they were but we simply don’t know.

& what of the marriage dance of the scorpion?

Do whales breach from exuberance

or for some sort of navigational reason?

What does the ant queen know or do to provoke such undying devotion?

What of the coelacanth & the neapilina—

not a fossil trace for 300 million years

then one day there she is swimming around.

In the mangrove swamps the fruit-bats hang from the trees

& flutter their great black wings.

How does a turnip sprout from a seed?

Creatures that hatch out of eggs & walk about on the earth

as if of their own volition.

How does a leaf unwind on its stem & turn red in the fall

& drop like a feather onto the snowy fields of the spinning world?

What does the shaman whisper into the ear of the beetle

that the beetle repeats to the rain?

Why does the common moth so love the light

she is willing to die? Is it some incurable hunger for warmth?

At least that I can understand.

How & why does the salmon swim thousands of miles back

to find the precise streambed, the very rock

under which it was born? God knows what that urge is

to be home in one’s bed if only to die. There have been dogs,

abandoned by families moving to other parts of the country

who have followed thru intricate cities,

over the wildest terrain —exhausted & bloody & limping—

a trail that in no way could be said to exist,

to scratch at a door it had never seen,

months, in cases, even years later.

Events such as these cannot be explained. If indeed

we are made of the same stuff as sea kelp & stars,

what that stuff is we haven’t any idea.

The very atom eludes us.

Is it a myth & the cosmos an infinite series of Chinese boxes,

an onion of unending minusculation?

What would it look like apart from the grid of the language—

cut loose from its names?

Is there no solid ground upon which to plant our molecular flag?

What of the microorganic civilizations

living their complex domestic histories out in the roots of our hair?

Is there life in the stars?

Are there creatures like us weeping in furnished rooms

out past the solar winds in the incalculable dark

where everything’s spinning away from everything else?

Are we just configurations of energy pulsing in space?

As if that explained this!

Is the universe conscious? Have we lived other lives?

Does the spirit exist? Is it immortal?

Do these questions even make sense?

& all this weighs on me like a verdict of exile.

I brush back the curtain an inch.

It flutters, as if by some ghostly hand.

Now Marie’s light is off & the world is nothing again,

utterly vacant, sunyata, the indecipherable void. How awesome

& sad & mysterious everything is tonight.

Tell me this, was the Shroud of Turin really the deathshroud of Jesus?

What of those tears that gush from the wounds

of particular icons? Don’t tell me they don’t;

thousands of people have seen them.

Did Therese Newman really survive on a wafer a day?

& the levitations of Eusapia Pallachino & St. Teresa.

& Salsky who suffered the stigmata in that old Victorian house

on Oak Street across from the Panhandle

on Good Friday. With my own eyes I saw them—his palms full of blood.

Where does everything disappear that I loved?

The old friends with whom I would wander about

lost in rhapsodic babble, stoned, in the dark:

Jim Fraser, Guarino, Steve Parker & Mednick & Burke—

squabbling & giggling over the cosmos. That walk-up

on 7th Street overlooking the tenement roofs of Manhattan.

Lovely Elizabeth dead & Ronnie OD’d on a rooftop in Brooklyn

& Jerry killed in the war & the women—those dark,

furtive kisses & sighs; all the mysterious moanings of sex.

Where did I lose the addresses of all those people I knew?

Now even their names are gone: taken, lost, abandoned,

vanished into the blue. Where is the OED

I won at Brooklyn College for writing a poem

& the poem itself decades gone, & the black & gold Madison

High School tennis team captain’s jacket I was so proud of?

Where is that beaded headband? The marvelous Indian flute?

That book of luminous magic-marker paintings Eliot did?

& where is Eliot now? & Greg Marquez? & Marvin Torfield?

Where are the folding scissors from Avenida Abancay in Lima?

Where is the antique pocket watch Rosalind Eichenstein gave me:

I loved it so—the painted shepherd playing the flute

in the greenest, most minuscule hills.

I bet some junkie on 7th Street took it

but there’s no way now to find out. It just disappeared

& no one & nothing that’s lost will ever be back.

How came a cuneiform tablet unearthed by the Susquehanna?

Why was Knossos never rebuilt?

What blast flattened the Tunguska forest in 1908?

& those things that fall from the sky—manna

from heaven & toads & huge blocks of ice & alabaster

& odd-shaped gelatinous matter—fafrotskis

of every description & type

that at one time or another have fallen out of the sky?

The alleged Venezuelan fafrotski—what is it exactly

& where did it come from?

& quarks & quasars & black holes... The woolly mammoth,

one moment peacefully grazing on clover in sunlight,

an instant later quick-frozen into the arctic

antediluvian north. What inconceivable cataclysm occurred?

How did it happen?

What would my own children have looked like?

Why is there always one shoe on the freeway?

Why am I shivering? What am I even doing

writing this poem? Is it all nothing but ego—my name

screaming out from the grave?

I look out the window again. How strange,

now the tobacco shop on the corner is lit.

A gaunt, mustachioed figure steps to the doorway & looks at my window

& waves. Why, it’s Fernando Pessoa!

I wave back—Fernando! Fernando! I cry out.

But he doesn’t see me. He can’t. The light snaps off.

The tobacco shop disappears into the blackness, into the past...

Who was the ghost in the red cape who told Henry IV he would die?

What of those children raised by wolves & gazelles?

What of spontaneous human combustion—those people

who burst into flame? Is space really curved?

Did the universe have a beginning

or did some sort of primal matter always exist?

Either way it doesn’t make sense!

How does the pion come tumbling out of the void

& where does it vanish once it is gone?

& we too—into what & where do we vanish?

For the worms, surely we too are meat on the hoof.

Frankly it scares me, it scares the hell out of me.

The back of my neck is dripping with sweat...a man

with a fever located somewhere along the Pacific Coast

in the latter half of the 20th century by the Julian calendar:

a conscious, momentary configuration; a bubble in the stew;

a child of the dark. I am going to stand up now if I can,

—that’s what I’m going to do—

& make my way to the kitchen

& find the medicine Mary told me was there.

Perhaps she was right. Perhaps it will help me to sleep.

Yes, that’s what I’ll do, I’ll sleep & forget.

We know only the first words of the message—if that.

I could weep when I think of how lovely it was

in its silver case all engraved with some sort of floral design,

the antique watch that Rosalind gave me years ago

on the Lower East Side of Manhattan

when we were young & in love & had nothing but time—that watch

with its little shepherd playing a flute on the tiny hillside,

gone now like everything else.

Where in the name of Christ did it disappear to—

that’s what I want to know!

I got a letter from an old acquaintance in New York

asking me to send some of my prose poems

to her literary magazine, Unhinged.

I should have known better.

In the old days she’d fluttered about

the coffee houses baring her long teeth.

We’d smile up politely and cover our throats.

But time makes you forget & ambition got the better of me

& a week later I got my poems back with a terse note:

Sorry, but this third-rate pornographic crap isn’t for us.

& may I point out it is presumptuous of you

not to have enclosed a self-addressed stamped envelope.

Just who in hell does little Stevie Kowit think he is?

I was nonplussed.

I sent a stamp back with a note explaining

that I hadn’t thought I was submitting to her magazine

so much as answering her letter.

I received a blistering reply:

Who was I kidding? What I had sent was a submission

to Unhinged, pure & simple.

In passing she referred to me as juvenile,

adolescent, immature, a sniveling brat, an infant

& a little baby—

truly the letter of a raving lunatic.

I suppose it would have been best to have ignored it,

forget the whole thing,

but that little Stevie Kowit business started eating at me,

so I dropped a one-liner in an envelope & sent it off:

Dear C, you are a ca-ca pee pee head.

I saw her once, briefly,

in the park

among the folk musicians

twenty years ago—

a barefoot child of twelve

or thirteen

in a light serape

& the faded, skintight levis

of the era. I recall

exactly how she stood there:

one foot on the rise

of the fountain

finger-picking that guitar

& singing

in the most alluring

& delicious voice,

& as she sang she’d

flick her hair

behind one shoulder

in a gesture that meant nothing,

yet I stood there

stunned.

One of those exquisite

creatures of the Village

who would hang around

Rienzi’s & Folk City,

haunting all the coffee houses

of MacDougal Street,

that child

has haunted my life

for twenty years.

Forgive me.

I am myself reticent

to speak of it,

this embarrassing infatuation

for a young girl,

seen once, briefly,

decades back,

as I hurried thru the park.

But there it is.

& I have written this

that I might linger at her side

a moment longer,

& to praise the Alexandrian,

Cavafy, that devotee

of beautiful boys

& shameless rhapsodist

of the ephemeral encounter.

Cavafy, it was your song

from which I borrowed

both the manner & the courage.

She was sensuous to a fault

& perfectly willing

though somewhat taken aback.

In fact, at first,

she noticed no one at the door at all.

“Down here!... down here!...”

I shrieked.

—Need I add that once again

I left unsatisfied.

Sometimes when I’m not there to defend myself

the friends start playing Kowit.

Right from the start, the game,

begun with what seemed nothing

if not innocent affection,

takes a nasty turn:

from quietly amused to openly derisive,

ruthless, scathing, & at last

maniacally sadistic—

a psychopathic bacchanal of innuendo,

malice & vindictive lies.

It’s jealousy & spite is what it is of course.

They’re rankled by my talent & integrity,

the editors & fancy women who surround me.

So Kowit’s torn upon the rack

& barbecued alive

& chewed out of his skin like a salami

till there is nothing left of him

but blood & phlegm & scat

& fingernails & teeth

& the famous Kowit penis

which is passed about the room

to little squeals of laughter,

like a ridiculous hat.

One fine morning they move in for the pinch

& snap on the cuffs—just like that.

Turns out they’ve known all about you for years,

have a file the length of a paddy-wagon

with everything—tapes, prints, film...

the whole shmear. Don’t ask me how but

they’ve managed to plug a mike into one of your molars

& know every felonious move & transgression

back to the very beginning, with ektachromes

of your least indiscretion & peccadillo.

Needless to say, you are thrilled,

though sitting there in the docket

you bogart it, tough as an old tooth—

your jaw set, your sleeves rolled

& three days of stubble... Only,

when they play it back it looks different:

a life common & loathsome as gum stuck to a chair.

Tedious hours of you picking your nose,

scratching, eating, clipping your toenails...

Alone, you look stupid; in public, your rapier

wit is slimy & limp as an old bandaid.

They have thousands of pictures of people around you

stifling yawns. As for sex—a bit

of pathetic groping among the unlovely & luckless:

a dance with everyone making steamy love in the dark

& you alone in a corner eating a pretzel.

You leap to your feet protesting

that’s not how it was, they have it all wrong.

But nobody hears you. The bailiff

is snoring, the judge is cleaning his teeth,

the jurors are all wearing glasses with eyes painted open.

The flies have folded their wings & stopped buzzing.

in the end, after huge doses of coffee,

the jury is polled. One after another

they manage to rise to their feet

like narcoleptics in August, sealing your fate:

Innocent... innocent... innocent... Right down the line.

You are carried out screaming.

& I had expected so much.

All the big kahunas would be there—

the New York literati & foundation honchos

& publishing magi & hordes of insouciant groupies

& millions of poets—

the shaggy vanguard in green adidas snapping their fingers,

surrealists whirling about by the ceiling

like adipose St. Teresas in mufti,

Bolinas cowboys & tatterdemalion beatniks

& Buddhists with mandarin beards & big goofy eyes

& Iowa poets in blazers & beanies

& Poundians nodding gigantic foreheads.

What tumultuous applause would erupt when I stepped

to the stage. What a thunder of adoration!

The room would be shaking.

The very city would tremble.

The whole damn Pacific Plate start to shudder.

One good jolt & everything west of the San Andreas

would squirt back into Mesopotamian waters

& this time for good—

jesus but they would love me!...

Except when I got to the place it was tiny,

a hole in the wall,

& only a handful had shown up

& as soon as I walked to the front of the room

a kid started whining,

a chap in the second row fell asleep

& a trashed-out punk rocker with a swastika t-shirt,

drool on his chin & arms down to his knees

started cackling out loud. The razor blade

chained at his throat bounced up & down.

Somewhere a couple must have been screwing around

under their seats—I heard tongues

lapping it up, orgasmic weeping,

groans that grew louder and louder.

The kid wouldn’t shut up.

The sleeper started to snore.

Potato chip eaters in every direction

were groping around in tinfoil bags

while the poetry lover, my host,

was oohing & aahing in all the wrong places.

I looked up politely. Couldn’t they please,

please be a little more quiet.

Somebody snickered. There was a slap

& the brat started to bawl.

Someone stormed out in a huff slamming the door.

Another screamed that I was a pig & a sexist.

A heavy-set lady in thick mensa glasses leaped to her feet

& announced that she was a student of Mark Strand.

In the back, the goon with the tattooed shirt

& the blade was guffawing & flapping his wings.

What could I do?

I read for all I was worth, straight from the heart,

all duende & dazzle—

no one & nothing was going to stop me!

Inspired at last, I read to a room

that had fallen utterly silent.

They must have been awed.

I wailed to the winds like Cassandra,

shoring our language against the gathering dark.

I raged at the heavens themselves

& ended the last set in tears, on my knees....

When I looked up it was night & I was alone

except for an old lady up on a stepladder

scrubbing what looked like glops of shit off the wall

& humming.

The place stank of ammonia.

Thank you so much

had been scribbled over my briefcase in lipstick

or blood. Someone had stepped on my glasses,

lifted my wallet,

& sliced off all of my buttons,

half of my mustache,

& one of my balls.

In a downtown San Jose hotel,

exhausted & uptight & almost broke,

we blew 16 colones & got stewed on rum.

You lounged in bed

reading Hermelinda Linda comics

while I stumbled drunk around the room

complaining

& reciting poems out of an old anthology.

I read that Easter elegy of Yeats’

which moved you,

bringing back that friend of yours,

Bob Fishman, who was dead.

You wept. I felt terrible.

We killed the bottle, made a blithered

kind of love & fell asleep.

Out in the Costa Rican night

the weasels of the dark held a fiesta

celebrating our safe arrival in their city

& our sound sleep.

We found our Ford Econoline next

morning where we’d left it,

on a side street, but ripped

apart like a piñata,

like a tortured bird, wing

window busted in, a door

sprung open on its pins like an astonished beak.

Beloved, everything we lost —our old blues

tapes, the telephoto lens, the Mayan priest,

that ancient Royal Portable I loved—

awoke me to how tentative & delicate

& brief & precious it all is, & was

for that a sort of aphrodisiac—though bitter

to swallow. That evening,

drunk on loss, I loved you

wildly, with a crazy passion, knowing

as I did, at last, the secret

of your own quietly voluptuous heart—you

who have loved always with a desperation

born as much of sorrow as of lust,

being, I suppose, at once unluckier,

& that much wiser to begin with.

Broken fence thru the mist.

Bitter fruit of the wild pear

& vines full of berries.

The stone path

buried in brambles

& mud

& the shack in ruins,

rotted thru

like an old crate:

half the roof caved in.

The whole place

gone to weed & debris.

Someone before me

sick of his life

must have figured this

was as far as he’d get

& nailed it up

out in the void,

then died here

or left

decades ago.

A swallow

skitters among the beams

& flies out

thru the open frame of a window.

Now nothing inhabits the place

but tin cans

covered with webs,

a mattress,

a handful of tools

busted and useless—

& myself

where he stood

here in the doorway,

in mist,

high up over this world.

Trees & flowers dripping with cold rain.

I am translating a poem by Domingo Alfonso

called “Crossing the River.”

When I lift my head from the page it is night.

I walk thru the rooms aware of the shapes

that loom in the silence.

In the bedroom, Mary has fallen asleep.

I stand in the doorway & watch her breathing

& wonder what it will be like

when one of us dies.

In 8 years

we have not been apart for more than a few days.

The cat drops to my feet & sashays past me.

I open the side door. Outside

there is no sound whatsoever. If things

call to each other at this hour of night

I do not hear them. Vega alone

gleams overhead, thousands of light years

off in the region of Lyra.

The great harp is still.

described himself as “a poet, essayist, teacher, workshop facilitator, and

all-around no good troublemaker.” A member of the Jewish Voice for Peace,

he lived in Potrero, California with his wife Mary and several companion animals.

He taught poetry workshops in San Diego, and his handbook for writing poetry, In

the Palm of Your Hand: The Poet’s Portable Workshop, is widely used.

His most recent collections include The Gods of Rapture (City Works Press,

2006) and The First Noble Truth (University of Tampa Press, 2007).

His book of new and selected poems, Cherish: New and Selected Poems, is forthcoming

from the University of Tampa Press in spring 2015.

stevekowit.com

In Memory of Steve Kowit