When I read that the novelist Susan Choi, in her quest for her Korean literary roots, had never heard of Richard E. Kim or his 1964 novel, The Martyred, I was dumbstruck. The man and his book have had an ongoing presence in my memories for decades. I was there at the beginning, while it was being written, then a witness to the phenomenal success of the novel throughout the world. Choi, daughter of a Korean father, notes in her foreword to the 2011 Penguin Classics republication of The Martyred that “Richard K. Kim had never been discussed at the Asian American reading group, he had never appeared on the syllabus.” Even after an older Korean man gave her a copy, the novel sat unopened on her bookshelves for another decade.

Fame is fleeting, and obscurity looms. But still, not even to know of Kim’s existence. After all, how many Korean writers have ever enjoyed such international recognition and prominence?

When I visited Kim (that’s how we addressed him; never Richard) at his home in Shutesbury, Massachusetts, in 1968, he showed me a three-tier, glass-front bookcase filled with editions in many languages. I was struck—and he was amused—by the German translation with an analytical pamphlet wrapped to the book with cellophane.

No one expected the novel to take off the way it did. The publisher, George Braziller, normally an outlet for art books and some important poets, never before had experienced a bestseller, scrambling to outsource printing as U.S. sales reached 60,000 hard-cover copies. The rush began with a laudatory full-page review in the St. Louis Post Dispatch and was followed by many more, including Chad Walsh’s front-page review in The New York Times Book Review of February 16, 1964, in which he said:

...his purpose here is not to tell the deeds of war but to probe the involutions and ambiguities of conscience—the meaning of suffering and of evil and holiness, the uncertain boundaries between illusion and truth. This he has done with a skill so great it is almost invisible.

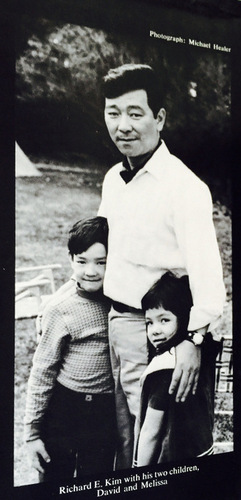

Life magazine, one of this country’s most successful weeklies in the mid 1960s, published a photo feature called “Best-Selling Korean” with Kim; his wife, Penny, on a backyard swing; and their two children, David and Melissa, sitting on their father’s lap. It was rare then as it is now for a new writer to take up pages in a magazine with a circulation of more than eight million.

I met Kim in Iowa City fifty-five years ago, in 1960. He was my officemate in a converted army barrack that housed the freshman writing graduate assistants. Before I actually saw him in person, I had heard much about him and viewed his photograph—stern-faced and seemingly foreboding. Just in his late twenties, he already had been an officer in the South Korean Army during the Korean War, a general’s aide, and eventually one of the two Koreans to serve on the UN Truce Team. He came to Iowa with an MA from the Johns Hopkins’ writing program. I was less than a novice, still bewildered that they had let me into the program, half expecting to be revealed as a clerical error. He—the idea of him—intimidated me before I even met him.

|

|

And yet we became good friends, to the point where I stood with him when he applied for his American citizenship, drove him to an army-navy surplus store in Cedar Rapids for our winter coats, and brought Penny and their first child, David, home from the university hospital. Those were pre-Pampers days, when all diapers were cloth and delivered by a service. I remember Kim pacing around their living room, constantly reaching into the crib to check the newborn’s diaper, and changing at the slightest dampness, despite Penny’s urgings to relax. Hardly a stern, foreboding man.

With his MFA he got a position teaching in the MFA program at the University of Massachusetts in Amherst, where I visited twice and saw him in New York several times to receive copies of his two books after The Martyred. He moved to teach at Long Beach State and San Diego State, and we lost touch, mainly because of my own personal dilemmas. I still regret that very much. If that had been a time of email and cell phones, I’m sure we would have stayed in contact.

But back to Susan Choi and her ignorance of his name. It’s not just that he wrote a well-reviewed novel. What happened was more like what’s said about Lord Byron—he woke up one morning and found himself famous.

The Martyred stayed on The New York Times bestseller list for twenty weeks, selling more than 1,000 copies a day in March 1964. It was translated into ten different languages, and made into a play, an opera, and a film. Pearl S. Buck, herself a Nobel Prize winner, predicted, “If this young man continues to do so well as this, he will someday be worthy of the Nobel Prize.”

And Kim was nominated for the prize in the early 1980s. By that time The Martyred had received a previous nomination for the National Book Award and Kim, a Guggenheim and National Endowment for the Arts Literary Fellowships.

His next novel, The Innocent, in 1968, after a big—for the time—advance from Houghton Mifflin, received mediocre reviews as it continued the story of the first novel’s narrator, Captain Lee, now a major. That novel is twice as long as The Martyred. I remember how nervous Kim was about it and his worries about its reception. It’s very different to be a suddenly discovered unknown than to be a writer who has a good part of the world looking over your shoulder as you type. At least that’s how it was in Kim’s mind, and he was not wrong, at least in his anxiety over being judged by the standard of his first book.

Here’s Kim on being a writer in America in a 1993 interview:

When The Martyred attracted all that attention, I learned about the writing game in this country—about agents, publicists, public relations, people, talk shows. It was flattering and seductive, but it was also scary and unpleasant.

I remember his anxiety back in Iowa City when his was about to be interviewed for a Korean broadcast of the Voice of America. Hours before the phone call he told me he was blanking and feared he had forgotten his native language. Of course, he hadn’t.

Heinz Insu Fenkl, in his introduction to the Penguin Classic edition of The Martyred, attributes timing to the tepid reception of The Innocent when it was released. The anti-war sentiment during the Vietnam War, he says, made many critics and readers uncomfortable and negative.

Kim supported that war because of his antipathy to Communism from his Korean War experience, including a pre-war childhood in the North. During a meal in a New York Korean restaurant he told me he thought it necessary to stop the spread of Communism, perhaps conflating the North Vietnamese with the North Koreans. He also warned me that the food was very spicy.

Ironically, anti-war protesters burned down the building that housed the Iowa office we shared. If it matters to anyone, I was opposed to the war from the beginning, marched and carried signs, though Kim and I never argued about it.

The Innocent hasn’t been reprinted. But Kim’s third book, Lost Names: Scenes from a Korean Boyhood, does have a 2011 edition from The University of California Press. Fenkl calls the work “a collection of loosely autobiographic stories,” and others refer to it as that. But Kim told me it was essentially about the facts of his early life. Of course, the first publication came years before the popularity of memoirs, when all stories, no matter how close to real events, were considered fiction.

The title story, “Lost Names,” tells of a time during Kim’s youth in North Korea when the Japanese conquerors of all Korea forced the natives to climb to a Shinto temple to receive Japanese names that replaced their real Korean names.

Kim is quoted as saying he had no animosity toward the Japanese. But I remember an embarrassed confession he made to me. Penny, not yet his wife, was taking courses at NYU, and he waited in a hallway outside a classroom for her. A young Japanese man, recognizing Kim as a fellow Asian, came up to him to chat. Kim lost it, ranting at the man and chasing him away. As he recounted what he did, he admitted his shame.

In Lost Names, Kim writes of his father, who was a national hero in Korea for his resistance to the Japanese occupation and to the North Koreans. Despite the father’s reputation, because of forced retirement rules in South Korea at the time, he became a man without a role at a relatively young age. In that, ironically, he may have prefigured his son’s becoming forgotten.

Kim never wrote another work of fiction after Lost Names in 1971. He did maintain a career in the literary world—translating, representing Korean authors, compiling photo books, writing Korean newspaper columns and a children’s book, and helping produce and narrate documentaries in Korea. Over the years I received rumors that he was back in Korea, which he was for a time. But I’m not sure how he divided his residences. But his obituary reports that he died in Shutesbury in 2009 with his family around him. His obituary noted memorial donations should be sent to a hospice. In the years I knew him he was a heavy smoker. Sad as I am that I let the friendship fade, I’m sadder that he gave up writing.

|

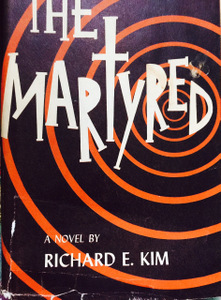

One detail I share with Susan Choi is a copy of The Martyred on

my bookshelves. But mine was autographed on 12/25/63, and I read

it immediately. I don’t know if Kim’s choice of Christmas day

was deliberate, but it is ironic timing for the novel in which Christian

belief lies at the core of the story and the characters’ torments.

[At left: The dust jacket of Cummins’ copy]

|

The novel is part mystery and part existential conundrum. The narrator, Captain Lee, an intelligence officer, is given the assignment of establishing what actually happened when the North Korean communists shot twelve Christian ministers. His superior, Colonel Chang, hopes to turn the event into useful propaganda by establishing that the murdered ministers were martyrs. Captain Lee first must interrogate two surviving ministers, Mr. Shin and Mr. Hann. Chang wishes to prove they lived because they betrayed those killed. What actually happened is much more tangled, Lee’s investigation complicated by Mr. Shin’s initial silence and several reversals in his later explanations. Complex questions of faith and belief emerge, and what had started as a search for specific information becomes an existential quest into the essence of human existence in a tragic world.

While the question of who betrayed the ministers dominates the story, less space is devoted to a perhaps even greater act of betrayal. The Chinese communists have entered the war, and the overwhelmed South Korean army is about to abandon the already bombed out city of Pyongyang. Captain Lee describes the view from his office window in the early pages of the novel: “From the white-blue November sky of North Korea, a cold gust swept down the debris-ridden slope, whipping up here and there dazzling snow flurries, smashing against the ugly, bullet-riddled buildings of Pyongyang.” The army deliberately fails to warn the population that an even greater destruction is about to descend.

War seems to be an impetus for such works of literature. Kim dedicated The Martyred to Albert Camus and quotes him for an epigraph. Camus’ writings sustained him through the war.

The Martyred shares much with The Plague. Camus’ characters, though memorable in themselves, are more representative of various beliefs and approaches to the crises of this world. Kim’s characters also reveal ways of behaving and relating to the extremes of war, suffering, and death. How should we behave? What should we do when faced with a moral dilemma? What should we believe? What must we do to sustain ourselves and others?

Fenkl, in his introduction, reports that Kim had been disappointed by 20th-century American literature for failing to be “the voice and the conscience of the people.”

That revelation explained to me why Kim asked the same question every time the Iowa fiction sections gathered for a joint session. We’d all talk about a work for an hour or two, but near the end of the period, Kim, sitting in the back of the room, would raise his hand and ask in the guise of an inscrutable Oriental, “Is this story?” He never dropped his articles in conversation. Why then? It was mysterious and befuddling.

I understand now that Kim had a different conception of what a story should be than the rest of the people in that room. He wasn’t interested in human interaction as such, but rather what people did or should do at times of existential crisis. For Kim, his fictional imagination was inseparable from his deepest concerns. Addressing them, he believed, is what fiction should do.

In many ways the first half of The Martyred resembles a traditional mystery novel, with variations of familiar plot and character matters, and as in all mysteries essential explanations are contained in backstory that the seekers must unearth. It’s almost exactly in the middle—after the revelations of the captured North Korean explain what actually happened with the ministers—that the novel turns from more conventional mystery detection to existential mysteries and unknowns. That’s not to say, the second half doesn’t offer several crucial surprise revelations; but none of the other characters were seeking or expecting them.

One commentary sums it up:

With strong existentialist themes, the story deals with issues of human suffering, the meanings of truth, the human conscience, and the nature of good and evil. The novel addresses larger questions about Christianity itself as well, exploring issues of faith, hope, confession, martyrdom, and betrayal.

Referring to Christian mysteries, Captain Lee notes: “I’m not much for mysteries.” At bit later, “I have no use for fairy tales.” He sympathizes with the suffering and despair of the Christians, but he does not love them. The question of fairy tales lies at the heart of belief and responsibility.

Colonel Chang, needing twelve martyrs for propaganda purposes, cares nothing for religion. “If there really is a god who can observe from high up in heaven what we down here are doing,” he says, “it surely must look rather childish.”

But the novel reveals that doubt is widespread. Ultimately, Mr. Shin—who sacrifices himself by lying about what happened to the murdered ministers to protect their memory—reveals that he does not believe: “I found only man with his sufferings...and death, inexorable death!” Mr. Shin finally urges: “Bear your cross with courage, courage to fight despair, to love man, to have pity on mortal man.”

When asked if he despises the Christians, Captain Lee answers that it’s the deception that bothers him, the Christians being lied to. “And meanwhile the people continue to suffer, continue to die, deceived from birth to death.”

At the end, Lee receives conflicting reports of Mr. Shin’s fate—that he is dead, that he is being seen all over the North, as if resurrected. He serves as the doubter who provides meaning and comfort to so many.

I’m reminded of the ending of Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, where Marlow, the narrator, haunted by his memory of Mr. Kurtz’s last words—“The Horror! The Horror!”—will not tell Mr. Kurtz’s intended the truth of what happened to her fiancé, as much as he hates a lie. He allows her to exist in her delusion, for to do otherwise would destroy her. Was Kim influenced? I know that he admired Conrad and identified with him as an author who also wrote in a third language.

On the closing pages Captain Lee joins the refugees in a national song “with a wondrous lightness of heart hitherto unknown to me.” Note that it is not a hymn. But he has accepted the others as “my people” and experiences a human connection.

At the conclusion of his Times review, Chad Walsh speculates on the ambiguity of the novel’s ending:

Perhaps the novel is saying that mankind can live only by illusion, and that the saint is the unbeliever who preaches illusion, at whatever inner cost to his own rational integrity. Or perhaps it implies that the apparent illusion proclaimed out of love for mankind is not illusion at all; that indeed it is the only real thing in a world that is otherwise meaningless flux, horror, and chaos.

He concludes the The Martyred is “a magnificent achievement, and it will last.”

We should remind ourselves that we have experienced the novel in a country where we enjoy relative safety, able to focus on our personal fulfillment and happiness. But we have only to read a newspaper or watch TV news to realize how many millions exist amid flux, horror, and chaos. It’s the fear that lurks in our nightmares.

While rereading I was often moved by revisiting a story I already knew. Walsh is right that the novel is an achievement, but—unfortunately—he was wrong that it would last. May it be rediscovered and reborn.

* Webmaster’s Notes:

The title “Great Books Forgotten or Unknown” is borrowed with permission

from a blog created in 2007 by Contributing Editors Walter Cummins and Thomas E.

Kennedy.

Additional information about Richard E. Kim is available at these sites:

•

www.richardekim.com

•

Another War Raged Within, a review by Chad Walsh in The New York Times (16 February 1964)

•

Best-selling Korean: Kim writes a remarkable novel, an article in the “Books” section of Life magazine (20 March 1964, pages 125-126); includes photographs of Kim, his wife Penelope, and his children David and Melissa as toddlers