|

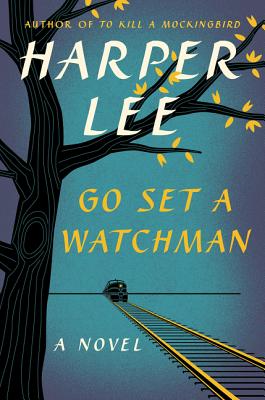

HarperCollins (2015)

|

The release of the Harper Lee novel, Go Set a Watchman, has been met with its fair share of criticism. Set 20 years past the events that take place in To Kill a Mockingbird, Go Set a Watchman tells the story of 26-year-old Jean Louise “Scout” Finch as she returns from New York City to her home in Maycomb, Alabama, where she struggles with deepening racial tensions.

It can be inferred that this story takes place around 1954 as the Brown v. Board of Education decision is alluded to, but never directly stated, throughout the novel. To Scout’s astonishment, her Aunt Alexandra, now living with 72-year-old Atticus, freely throws the N-word around during her everyday conversations. Scout feels the hostility between Maycomb’s white and black citizens.

She follows her father and would-be lover, Henry Clinton, to a citizens’ council meeting. The goal of the meeting is to discuss how to maintain segregation within Maycomb. Scout is shocked that Atticus would attend such a meeting and is horrified that he is introducing and sitting next to Grady O’Hanlon, a leading white supremacist and segregationist. It is here where the conflict of the story resides.

Go Set a Watchman deals primarily with Scout’s difficulties in accepting that her father isn’t the ideal picture of equality and humanity that she thought he was, which is also where critics tend to direct their anger.

Yes...Atticus is a bigot, which has To Kill Mockingbird loyalists up in arms. I’ve read several reviews that blast the decision to publish this sequel because it destroys the ideal vision of Atticus portrayed in Mockingbird. The irony is that Harper Lee’s audience shares the same disappointment in Atticus that Scout does.

The combination of the two novels put together is very disturbing. We, the audience, grew to love Atticus as seen through the eyes of his innocent daughter. Atticus is a symbol of incorruptible justice and freedom for all. However, in Watchman Scout is an adult who sees the harsh reality of racial prejudice present within Maycomb, the United States, and her father. I praise the novel’s ability to move beyond the commercial feel-good sentimentality of Mockingbird and deal with the dark realities of racism present within our society.

Towards the end of the novel, Scout has a confrontation with Atticus about his troubling beliefs. At the heart of Atticus’s issue with racial integration is the Supreme Court’s ruling in the Brown v. Board of Education case that outlawed segregation within public schools across the nation. Atticus is angered by the Supreme Court, and, in turn, the federal government, because he views this decision as a violation of the 10th Amendment. The 10th Amendment states: “The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people.”

Atticus believes that the federal government violated the Constitution by requiring all states to follow integration laws, even if not supported by a state’s government, such as his native Alabama. What is troubling is that Scout agrees with Atticus’s interpretation of the law on this point. She even criticizes the Supreme Court’s handling of Brown v. Board of Education, “and there went the Court just breezily canceling one whole amendment, it seemed to me.”

Scout later justifies the Supreme Court’s decision by saying that even though she disapproves of how they handled it, their decision was the right one.

Scout doesn’t realize that the Brown v. Board of Education doesn’t fly in the face of the 10th Amendment. In truth, the 10th Amendment has nothing to do with Brown v. Board of Education. Scout realizes that segregation is innately wrong from a moral perspective, but not necessarily a legal one. She misses an important point here, which is that segregation laws were unconstitutional from their inception.

In its opening lines, the Constitution announces that part of its purpose is to “secure the Blessings of Liberty” which is something that she and Atticus never mention. One can’t help but look at Scout’s vision of the law as Harper Lee’s vision. Scout, through both novels, seems to embody Harper Lee’s thoughts and life trauma. If Harper Lee really believed that the Brown v. Board of Education ruling was a violation of the 10th Amendment and that the Federal Government was acting in a tyrannical manner towards the South, then this shows a serious character flaw in Harper Lee herself.

Beware...I’m about to spoil the ending of the novel. Towards the end of the story, Scout cusses Atticus, basically disowning him. Scout’s Uncle Jack steps in by physically and emotionally confronting her about her treatment of her father.

Ultimately, Uncle Jack argues that there is no such thing as a “collective conscience” and that she has unfairly envisioned her father as God, when in reality he’s just a man with his own personal failings. Uncle Jack then persuades Scout that her objections to her father’s bigoted views make her a necessity to Maycomb.

The failure of the novel is that it lacks a well-developed resolution. Scout sides with her Uncle Jack, makes up with Atticus, and accepts his views on segregation, even though they do not coincide with her own. Lee’s message to her audience seems to be that the people you love will often have a standard of morality that doesn’t correspond with yours, so accept that and continue to love them if you can. Unfortunately, this message is over simplistic, underdeveloped, and anti-climactic.

My conjecture is that the lack of a developed resolution and message is why Go Set a Watchman went unpublished until now. It is easy to see how her editor could have made these same observations and told her to try again, which, for better or worse, she did.

has taught English Literature at William Fremd High School in Palatine, Illinois for ten years. In addition, he is a freelance sports journalist who specializes in the sport of boxing. His journalistic work has been featured in BleacherReport.com, BoxingInsider.com, MGM Resorts’ M life Magazine, and Boxing News Magazine. His style is a fusion between classic and gonzo journalism.